Will Barnet’s artistic journey is not just a reflection of his own creative talent, but also a testament to the diverse influences that shape an artist’s distinct style. Spanning nearly eight decades, Barnet’s career as a painter and printmaker exemplifies a quest for innovation and a deep appreciation for the artistic traditions that surrounded him. From the tumultuous era of the Great Depression to the dawn of the twenty-first century, Barnet’s oeuvre evolved amidst the shifting landscapes of art movements, from Social Realism to Abstract Expressionism. However, it was his engagement with Native American art that added a unique dimension to his work and contributed to the emergence of a genre that would later be known as Indian Space Painting.

The son of Russian immigrants who settled in Beverly, Massachusetts, Barnet’s siblings were all much older than he, and as a result, young Will had a rather solitary life that ultimately fostered the development of a vigorously independent individual, which was reflected in his artistic career. He realized at a young age that that becoming an artist would give him the “ability to create something which would live on after death.”1 He became determined that he would devote his lifetime to doing “what I desired most. . . . My desire was to paint humanity.”2

At the heart of Barnet’s artistic philosophy was a profound respect for the enduring legacy of art. He once expressed his aspiration to be like the Old Masters, whose works transcended time and mortality. He believed that “if the Old Masters were able to sustain interest right to the end there was no reason why a man living today couldn’t do it.”3 He adhered to a deliberate and rigorous process, which led one art writer to comment that Barnet “constructs his paintings, prints and watercolors as carefully as an engineer designs a bridge.”4 This reverence for artistic immortality fueled his dedication to creating something that would endure beyond his own lifetime—a sentiment that also resonates deeply with Native American artmaking.

Barnet’s fascination with Native American art was not merely aesthetic; it was grounded in a deeply philosophical exploration of spatial dynamics and cultural symbolism. Through his connections with artists of the Indian Space Painting movement, Barnet drew inspiration from the structures inherent in Native American visual and material culture. He underscored this influence in his work through the abstraction of form, flattening of space, and the interplay between positive and negative space—a hallmark of many Native American artistic traditions.

The Indian Space Painters were a loosely organized group of non-Native mid-twentieth-century Modernists active during the late 1940s and early 1950s. Notable among them were Gertrude Barrer (1921–1997), Howard Daum (1918–1988), and Peter Busa (1914–1985) among others. They sought to create a new form of American art wholly distinct from European predecessors and inspired by the aesthetic traditions of Indigenous peoples. Their work, characterized by all-over compositions, two-dimensional abstraction, and vibrant color palettes, was rooted in the visual forms of the Indigenous arts and material culture of the Americas, and pushed the boundaries of contemporary art.

While Barnet was not a formal member of the Indian Space Painting movement, its practitioners included close colleagues and students of his at the Art Students League who shared in or learned from his exploration of Indigenous art forms that deeply informed their artistic practices. Barnet in particular drew from a wide range of Indigenous sources, from Northwest Coast painting and carving to Pueblo pottery and Southwest design, weaving elements of their traditions into his own visual vocabulary. For Barnet, Indigenous art offered a more intriguing conception of space—a flattening of the artwork’s perspective and a certain ambiguity between positive and negative space that transcended the confines of traditional European aesthetics.

I wanted to get away from the three-dimensional idea of space, find a way to compress it into two dimensions. And the Indian art I saw in my youth and as an adult in visits to the Museum of Natural History and the Museum of the American Indian showed me the way. . . . Indian Space showed me the way of merging Indian and Western art together. It took me beyond Cubism in a search for American values.5

One of the most significant contributions of Barnet’s engagement with Native American art was his impact on future generations of artists. Through his teaching at institutions like the Art Students League, the Cooper Union, Yale University, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and his emphasis on Indigenous visual culture, Barnet inspired a new wave of creativity that reverberated throughout the art world. This included the contemporary Native American art movement by way of the career of Seymour Tubis, one of Barnet’s students and teaching assistants at the League. Tubis, whose work reflected Barnet’s lessons and ethos, was among the first instructors and a pivotal figure at the Institute of American Indian Arts, founded in Santa Fe in 1962. There, he continued Barnet’s legacy of integrating Indigenous forms and philosophies into contemporary artistic practice that he taught back to Native American students whose work combines Modernist techniques with their unique cultural traditions.

As we reflect on the legacy of Will Barnet, it is clear that his engagement with Native American art encompassed a meaningful dialogue—a mutual exchange of ideas and inspirations. While acknowledging the complexities of cultural influence, we must recognize Barnet’s role in fostering a deeper appreciation for Indigenous art and its enduring relevance in the broader landscape of American art. This relationship across time between Barnet, the Indian Space Painters, historic Indigenous art, and the modern Native art movement is being explored in the forthcoming exhibition Space Makers: Indigenous Expression and a New American Art at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, April 13–September 30, 2024.

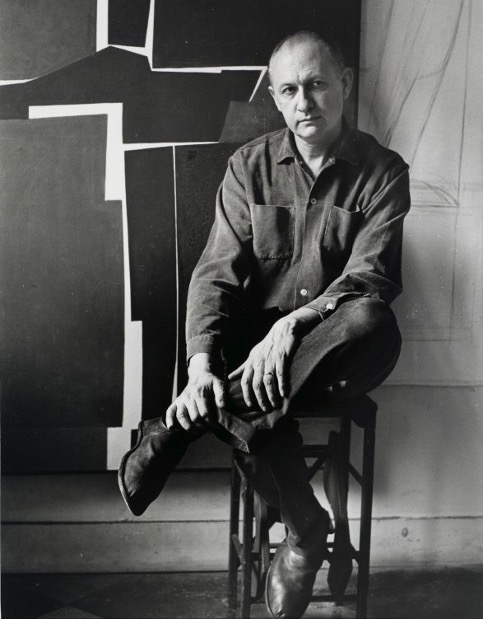

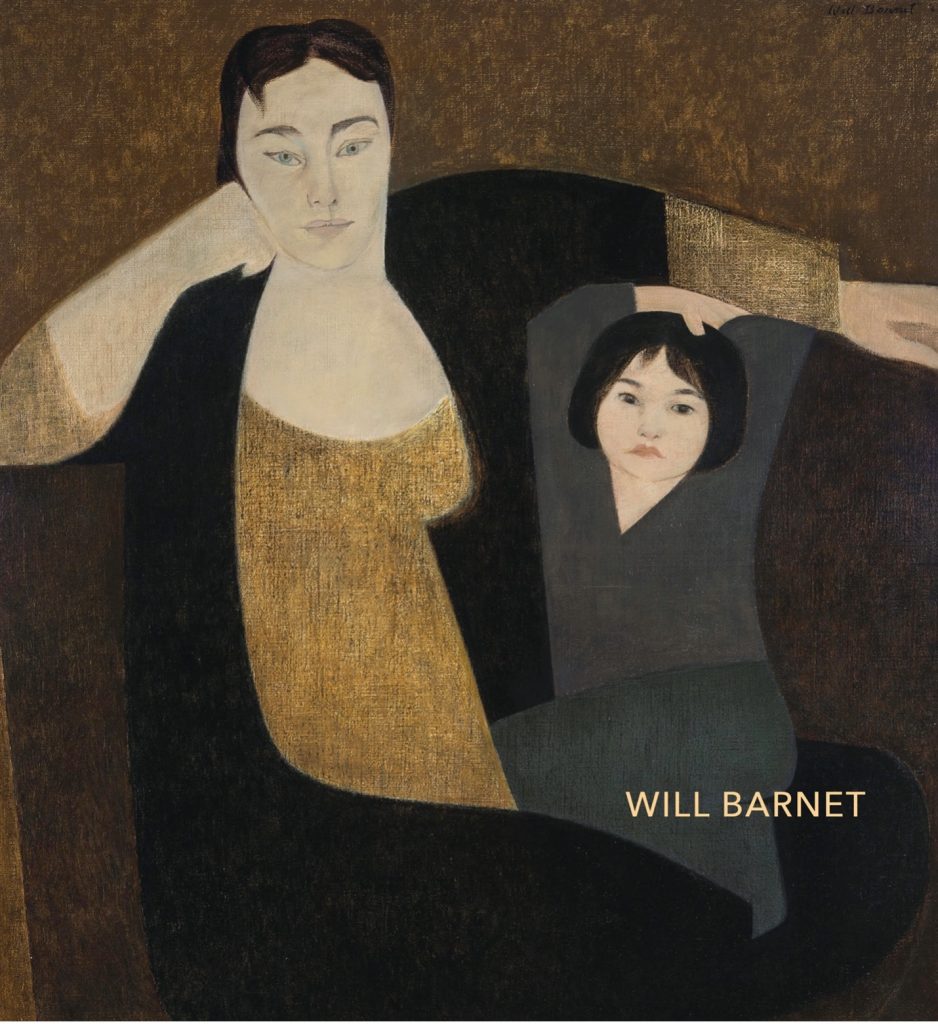

The forthcoming publication, Will Barnet, a comprehensive monograph published by The Artist Book Foundation, serves as a testament to Barnet’s enduring legacy and the mutually profound impact he and the Native American artistic landscape experienced during his career. Through scholarly essays, an extensive plate section, and a detailed bibliography, as well as thorough lists of exhibitions, awards, and collections, this monograph promises to offer a comprehensive exploration of the artist’s iconic imagery and his evolving relationship with Native American art. In celebrating the life and work of Will Barnet, the monograph not only pays tribute to a singular artistic talent but also acknowledges the rich tapestry of influences that shaped his extraordinary journey—an odyssey that continues to inspire and captivate audiences around the world.

Notes

1 Katherine French, “An Act of Memory,” essay in Will Barnet: My Father’s House, 14.

2 Barnet quoted in Richard Brown Baker, “Interview with Will Barnet,” January 20 and 26, 1964, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 37–38.

3 Ibid.

4 Orazio Fumagalli, “Will Barnet,” essay in Will Barnet; A Retrospective Exhibition (Duluth, MN: Tweed Gallery, University of Minnesota, 1958), n.p.

5 Will Barnet quoted in Barbara Delatiner, “Artist Explains His Indian Inspiration,” New York Times, April 28, 1996, 14.

__________________________

Author Bio:

The Artist Book Foundation (TABF) is a nonprofit art book publisher that celebrates artists’ lives and work through publications, related exhibitions, and public programs. TABF works collaboratively with artists, museum curators, art historians, and collectors to develop catalogues raisonnés, monographs, surveys, and exhibition catalogues. It is dedicated to preserving and celebrating the artistic legacy of acclaimed as well as underrepresented artists. With a focus on producing artist centered publications that delve into the lives and works of these remarkable individuals, TABF plays a vital role in fostering appreciation for the arts and their lasting impact on culture and society. Additionally, TABF’s book donations program provides access to the arts to the widest audience possible by delivering thousands of copies of their publications to underserved public libraries, schools, and prisons across the country.