How do conservators restore damaged art works, what does it cost, and how does it impact value?

By Isabel Thottam

Imagine walking through a beautiful exhibit of famous paintings at a museum. You look closely at a Picasso and lean forward in admiration. Suddenly, you lose your balance and, without thinking, latch onto the painting to catch your fall. Whoops. You’ve left a fist-sized hole in a million-dollar painting.

It may sound impossible, but it happens more often than you think. This year, a 12-year-old Taiwanese boy tripped and accidentally punched a hole in a $1.5 million Paolo Porpora oil on canvas. His accident is one of many unfortunate slip-ups to damage expensive works of art. In some cases, people purposely damage artwork. In 1990, a man sprayed sulfuric acid on Rembrandt van Rijn’s “The Night Watch.” This action was the third time someone purposely damaged Rembrandt’s famous work; vandals with knives slashed it in 1911 and 1975.

In the case of the Porpora painting, the boy’s family did not have to pay for the damages. Fortunately, the painting was insured and is currently undergoing restoration. But who spends the time and money to fix these valuable artworks when accidents happen? How much does it cost, and what does insurance cover? More important, how does one fix a painting with a hole in the middle of it, and does the artwork lose value due to the damages?

Enter the art conservator, the quiet hero who spends countless hours performing delicate work to restore and conserve damaged pieces of art.

Structural and Aesthetic Damage

Though people often refer to conservation and restoration as one entity, they have a few distinctions. Conservation is the profession and the starting point for a conservator, whereas restoration describes parts of the process.

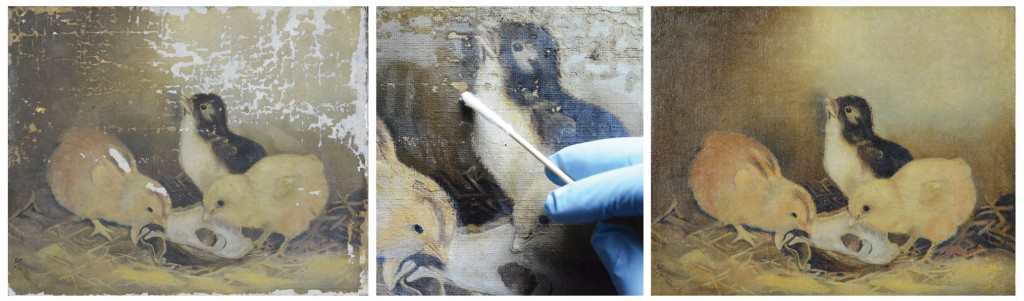

Beyond conserving the original materials, conservators consider the restoration side of their practice to encompass areas requiring fillers, colors, or coatings to reconstitute a missing component of the art. The process is tedious and an art form in itself. Art conservators see variations of damage, but they all fall into one of two categories: structural or aesthetic.

Structural damage might be the result of storage in an improper environment, the deterioration of materials, or poor handling practices. Human intervention falls into this realm and is a top contender for what causes the most damage to art. Aesthetic or cosmetic damages are due to the fact that the artwork has old varnishes, causing discoloration, or has paint flaking off the surface.

Conservators also experience inherent vice, a problem that occurs when the material the artist used is not compatible with the coatings an art conservator uses in restoration. This problem occurs most often with works of modern and contemporary art, because such artists use experimental acrylics, which are more sensitive than oils.

“[Contemporary artists] are creating multimedia works of art, and those are naturally harder to care for than a traditional painting,” says Ana Alba, an independent art conservator in Pittsburgh and founder and owner of Alba Art Conservation. “But our code of ethics is to use most things that are reversible because we can’t change the artist’s intent or chosen materials. However, I have treated cardboard before, and no one should expect that to last a thousand years.”

The Cost of Conservation and Restoration

Museums have access to technical equipment that independent conservators lack, according to Rhona MacBeth, a conservator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. For example, museums have X-ray machines, which allow conservators to look below the surface of paintings to document their condition and quality. Infrared cameras can cost $50,000 to $100,000, but conservators can also perform repairs with SLR (single-lens reflex) cameras that cost approximately $1,000.

“In a big museum like the MFA, we have a huge scientific department that can do an analysis of coatings to see how [a painting] was made,” explains MacBeth.

Independent art conservators typically do not own huge pieces of equipment. Instead, they pay to send samples to a lab for scientific analysis, later adding this expense to a customer’s bill.

“In the public realm, conservators will have an hourly rate, and a conservation treatment will either be charged according to that rate or a total project cost,” says Nicholas Dorman, chief conservator at the Seattle Art Museum.

Alba’s projects can range from simple cleanings of personal paintings for a few hundred dollars to more involved projects costing thousands of dollars, depending on the size and condition of the artwork. Alba bills her clients by the hour. If there’s a bigger issue, she’ll address that in her estimate.

Providing an estimate is part of the American Institute for Conservation’s code of ethics. Conservators must provide a treatment proposal with cost estimates and an examination report. The customer must sign it before any treatment can occur.

Peter Himmelstein, paintings conservator at Appelbaum & Himmelstein Conservators and Consultants in New York City, works for individuals and small institutions, noting that some clients pay out of pocket, whereas others receive grants to fund the conservation. He says a small painting with an average amount of restoration work can cost $800 to $1,000. A larger painting with damages can cost $10,000 to $15,000.

Grants to fund conservation come from a variety of sources. The National Endowment for the Arts awards grants annually, and New York State offers a $7,500 grant for treatment.

The MFA in Boston employs five conservators. Two are staff on yearly contracts, whereas others work on special projects funded through foundations or grants.

In some cases, insurance claims will pay for treatments, as was the case when the Taiwanese boy’s family did not have to pay for restoration efforts.

Himmelstein explains that there is all-risk art insurance, which covers liability for fire, flood, and theft. However, he says there is no professional liability insurance for conservators.

“Owners should expect to pay insurance while the art is in the conservator’s hands, but it does not cover the work,” says Himmelstein. “We provide insurance to the owner at a low-level amount for free, as $2,000 to $5,000 will cover most of it. For a more valuable painting, they can increase the coverage when needed—say, if it’s going to take four to five months to complete.”

Most museums don’t have listed policies. However, Himmelstein says that insurance in a museum will cover the cost of treatment if something is damaged and incurs a loss of value or if someone bumps into a piece of artwork. The insurance covers the cost of the treatment to repair the damage.

Between costs and insurance, conservation is an expensive business. “Oddly, people don’t seem to balk at spending money on cars or house maintenance, because these things have both utility and aesthetic importance,” says Dorman. “Although paintings can be quite valuable, their status as primarily aesthetic objects means people often consider conservation as something of a luxury—a luxury on top of a luxury, if you like.”

The Biggest Cost is Time

“Time, experience, and the training that people have is what customers are paying for,” says Himmelstein. “Conservation is time-consuming, so that’s where the cost is.”

Time accounts for the largest expense because conservation is labor-intensive. MacBeth and Dorman work with professional staffs to conserve and restore museum pieces. Moreover, museums often work on multiple pieces at once with various deadlines.

Conservators say that it can take two to three weeks to restore a painting. However, this timing can vary depending on a piece’s condition, the extent of damage, and the painting’s size. A large painting with extensive damage could take months and, in some cases, years.

“It’s very labor-intensive,” says MacBeth. “It could take a few days if it’s not a big intervention. For a tiny bit of restoration or surface cleaning, such as taking grind off the surface, it can happen in a day or two. But I have worked on paintings for years at a time.”

The Impact of Intervention

The life cycle of a painting varies depending on its condition, the materials the artist used, and the amount and quality of the restoration it has undergone.

“In recent decades, conservators have given considerable thought to … lengthening the period between treatments,” says Dorman. “We know that, even when we raise the flags of reversibility and minimal intervention, our work is precisely that—an intervention—and it has an impact on the art.”

Conservators and appraisers seem to agree that conservation doesn’t decrease a painting’s value. However, this factor depends on the conservator’s ability to restore the piece without changing anything about the art.

“While few forms of conservation treatment can really be said to be objective, conservators are trained to try to keep the visible signs of their interventions as unobtrusive as possible,” says Dorman.

“People argue [that] it would be better if no one ever touched it,” says MacBeth. “[But] it’s incredibly rare to come across an old painting that hasn’t been restored. If the restoration is done well, I’m not sure if it adds to the value. There’s always a bit of subjectivity here, depending on how someone believes [the restoration] to have been done.”

Scott Zema, an appraiser at Ark Limited Appraisals in Seattle, says that most canvas paintings have had restoration work done because canvas, in various forms, disintegrates over time.

“Restoration is a huge part of value determination,” says Zema. “If restored correctly, there is no loss in value. But you have to look at the quality of conservation and the amount of damage; it all comes into play in [affecting] the value.”

Alba explains that conservators cannot make damage disappear. Though they usually can do something, conservators might not be able to completely restore a piece, and the cost of treatment could outweigh the cost of the painting.

“The American school is different from the European school, which might be more stringent on cleaning. Here, it’s common practice to remove a varnish because you’re returning it back to the originally intended appearance,” says Alba. “But there have been big controversies on this [issue], such as the Sistine Chapel cleaning and at the National Gallery with a Rembrandt.”

Alba refers her clients to a local appraiser before agreeing to treatment, explaining that they will be able to better determine the market cost of the artwork, whether they need to conserve the piece, and how likely it is to resell.

Zema says that conservators can restore paintings with 50 percent or less damage. As long as the damage does not materially affect the original work, they can restore the painting without decreasing its value. Think of it this way: If a car needs a new engine and a new body, the owner needs to replace it with a new car.

“You don’t want to be filling in the face because of a hole in the canvas. If restoration has been done on a significant part, it won’t have much value,” Zema explains. “The value will never be what it would be without the big touch-ups.”

Structural and cosmetic damages can harm a work of art, and improper treatment could affect the value. The important thing to note, however, is that many paintings in great museums worldwide have undergone some type of restoration. But, as Zema points out, when restored correctly without significant damage, the artwork’s value will not change.

“These issues don’t always disturb the audiences who enjoy those paintings, because conservators have carefully treated the paintings to reduce the visual impact of such damages,” says Dorman.

MacBeth agrees, explaining, “If you do it in an educated way, it can be fun to see what happens after the restoration. Then you end up buying something that no one else realized was as beautiful as it is.”

Art lovers should not overlook the work of art conservators; without restoration and conservation, the paintings they enjoy in museums or their homes could disappear. Conservation does not devalue art; rather, it restores what was once beautiful so that audiences can continue to admire the artwork for years to come.

19 Comments

I am reopening my gallery Framing prices have changed I need to know what are the new framing charges in Pennsyvania

Any chance you can remove glue and stiff backing on an etching from the 20,30s in fact I have 6 to be done over thank you johnb

Fabulous article. And, you answered all of my questions. Thank you.

Sunday, September17, 2017

We have a portrait of an ancestor that needs to be cleaned. It is very large. Possibly, just a guess the width is 48 X 56 inches. To my knowledge, it has never been cleaned; probably full of wax & soot and you cannot the signature. No holes. One spot , not even as big as the head of a thumb tack where paint will need to be repaired.

Thank you,

Best regards,

Laura

Did you ever get your piece of your ancestor restored?

I forgot to mention this also. Kristin Deghetaldi is completely correct. I would avoid the use of the word ‘restoration’ as that is only a small component of what we do.

As a paper conservator with almost 10 years of experience I can say that this is a really well done article. A few quick points.

1) There is no such thing as a conservator or restorer that does ‘everything’ such as paper and paintings. Conservation is divided between paper, paintings, and objects. If you encounter someone who does say they do everything I would strongly suggest no using them.

2) There is no such thing a certification in this field. The only two accreditation systems for conservation are in for conservators living in Canada and those living in Europe. The closest you get to being ‘certified’ in conservation in the US are two peer reviewed status levels within the American Institute for Conservation (AIC), for which any competent conservator in the US should be. It basically means that we have been peer reviewed by other conservators and the organization for a basic level of ethics and competence. These two levels are called either PA (Professional Associate) or Fellow. A list of these conservators can be found through AIC’s website. I would not recommend using anyone who is not either a PA or a Fellow. I know of most of the conservators in this article and all are one of these two.

3) Almost every conservator trained in North America in the last 30 years will have gone through one of the graduate level conservation programs (for which their are about six). There are some exceptions to this but they are rare. These programs are basically med-school for art conservators. If you are looking into having something conserved I would make sure you use someone that has gone through one of these programs. Otherwise it is like using a doctor that never went through med-school or a lawyer that never went to law school. It doesn’t necessarily mean they won’t do a good job but you are definitely rolling the dice.

3) What this article does not say is that is that insuring a piece of artwork without a current appraisal will be a waste of money and therefore asking a conservator to insure your un-appraised artwork is also the same. I know of no insurance company that will meet a claim on a damaged piece of artwork on ‘stated value’. You can of course say your artwork is worth what ever you want, but unless you have it appraised there is no way an insurance company will pay anything on it. So when you bring your artwork to a conservator and they say they are ‘fully insured’ that is really just for client comfort and nothing more. It really won’t mean anything if you have to put a claim in. Most of the time if you are at a point where your artwork is of high enough value that you using a conservator, your artwork is covered under your home owners policy anyway or it will have a special rider on your policy.

Seth,

My wife and I have owned a Hudson School Pastel for the past 42 years. It is a prized possession. I have been doing some research and have found that the painting has many characteristics of the one found that had a copy of the Declaration of Independence behind the work. It has a beautiful hand carved frame, original glass and the back of the painting has never been removed. I contacted my state museum and they are not interested in helping me. My questions to you are, would an x-ray show if there is another piece of paper behind the painting and would it damage the work?

Thank You Seth

Thank you for your article I am 72 painter and Sculptor. I have been restoring my own collection of paintings for many years. The time I spend on restoring a painting and bring it back to life, is the best part of the day nothing gives me more pleasure. I have taken on restoring other people’s paintings in my retirement to earn some extra money and I think I’ve been under charging them if you could advise me as to pricing say per square inch what an average price might be I would greatly appreciate it. After reading your article I’m concerned about insurance in case there painting gets damaged or I damaged the painting. What type of insurance should I carry and how can I protect myself against liability? I know you can’t answer everyone that writes to you I would be happy to compensate you for your advice and information. I regret I did not make conservation my career your father must have been a wonderful man to do this for you. If interested I am listed art Fusion gallery in Miami. With all my thanks and gratitude Jeffrey Koster

You should probably refrain from “restoring” artworks unless you have received adequate training through a recognized graduate program. Would you read a book about dentistry and try and extract your own tooth? Probably not….conservation requires years of experience and a certain amount of baseline knowledge relating to the hard sciences. You can learn more about how to become a professional conservator on the American Institute for Conservation’s website here:http://www.conservation-us.org/

I am looking for an expert restoration expert for a Pieer Neffs 1578 painting with 6 or 7 chips in the paint.

Ron Gaiser, did you ever receive a response??

Hi,

We are professional art conservators/restorers with european education and over 35 years experiance.Please look at our web side and if you need our service please contact us.

Thank you

Andre & Barbara Bossak MFA

I could refurbish it for $1,000. Need to know if it’s on canvas or board? How bad are the chips?

I am looking for a oil painting expert restorer. I have a Pieter Neffs 1578 interior church painting that has several small chips.

Please look me up Brush Strokes Fine Art LLC Springfield VA. I have been working with oil restoration and conservation for a long period of time. http://www.anabela-artist.com/artrestorations/

I do art restorations. I have been doing it for over 35 years. Clients ship their pieces to me internationally. I have a huge client base in The Bahamas they ship to me here in Florida. I also have Florida clients as well. I can give you references of past work I have done. My biggest and most notable client is Gilbert Llyod from Llyods of London. I did about 40 pieces of his private collection that he had in his Bahamas residence. My contact information is 352-531-8762 if you would like to discuss your piece further.

Fresco Art co., inc. is a unique company specializing in the restoration, renovation oil paintings.

A brilliant article. I’ve been intrigued about the restoration process, the writer explains precisely the steps taken to repair a priceless piece of artwork.