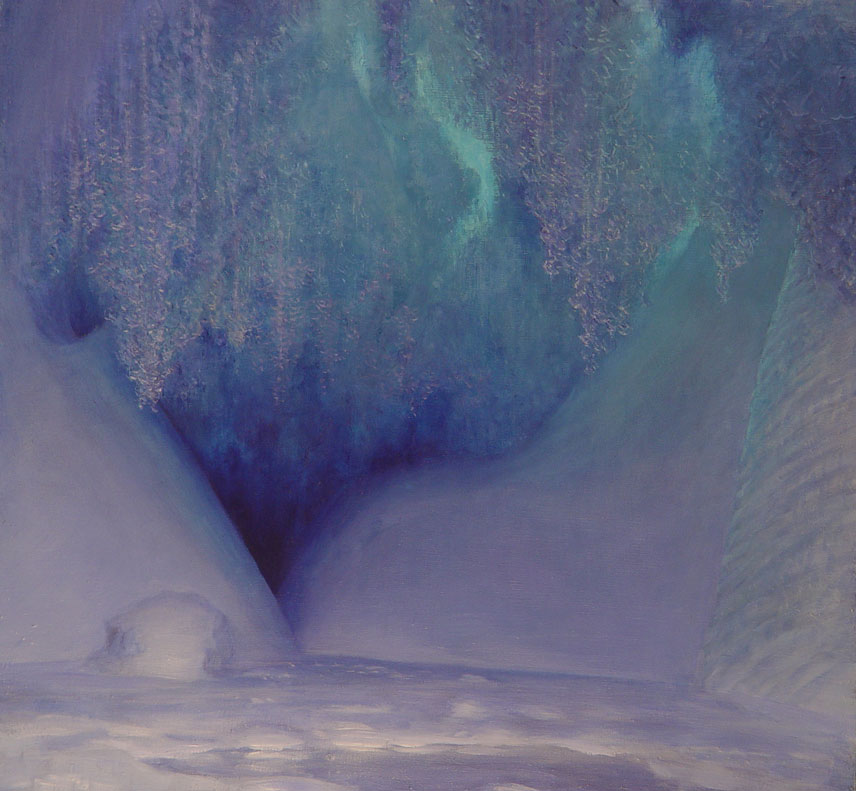

Intrepid painter David Rosenthal finds inspiration in the extremes of the Antarctic

The temperature was 30 below. The wind blew with a vengeance. It was blisteringly, achingly cold. At this temperature, watercolors freeze solid; oil paints turn to crayon—but David Rosenthal was ready to paint. In extreme weather conditions—and extreme geography—is where Rosenthal makes his art. And few, if any, artists have dared venture where Rosenthal has in pursuit of his craft: to Antarctica, the unforgiving landscape of the Earth’s frozen underbelly.

“I don’t care who you are. You don’t sit out in those conditions and do a plein air painting,” says Rosenthal. “It’s so austere, and it’s not friendly. It’s just this cold, icy, beautiful place. It’s a great experience to be there, but it’s not a heartwarming experience.”

Rosenthal, 62, whose home is in Alaska, has pioneered a path that accomplished artists rarely travel, and the many fits and starts and detours along his lifetime journey offer unexpected lessons about stubbornness, sensitivity, and art’s role in our planet’s health. Antarctica might not be heartwarming, but Rosenthal compensates with fire in his belly.

• • •

Born and raised in Maine, Rosenthal grew up exploring the great outdoors. At the University of Maine, he majored in physics, but he was distracted and disengaged. Increasingly, he picked up pen and paper and spent hours doodling, mostly sketching Maine’s abundant trees and hills. On a whim, he added art to his class schedule.

“The instructors treated me like I was slow because no one paints landscapes,” Rosenthal recalls. “They wanted me to do the latest cutting-edge whatever. To me, it just sounded like nonsense.” After college, he never took another art lesson. But he kept drawing—and painting—landscapes.

In 1977, at 23, Rosenthal crossed the continent for a summer job at a salmon-processing factory in Cordova, Alaska. For hours on end, he toiled on the canning assembly line and moved heavy loads to and from the freezer. During downtime, he took long hikes and marveled at the soaring glacial peaks embracing Cordova’s harbor. His supervisors, appreciating his hard work and moxie, offered him promotions and year-round employment. They gave him an apartment in the factory and agreed to keep his work schedule flexible so that he could head out on the trails to sketch.

In 1977, at 23, Rosenthal crossed the continent for a summer job at a salmon-processing factory in Cordova, Alaska. For hours on end, he toiled on the canning assembly line and moved heavy loads to and from the freezer. During downtime, he took long hikes and marveled at the soaring glacial peaks embracing Cordova’s harbor. His supervisors, appreciating his hard work and moxie, offered him promotions and year-round employment. They gave him an apartment in the factory and agreed to keep his work schedule flexible so that he could head out on the trails to sketch.

“I was not exposed very much to what [artists] were doing in the outside world or what they thought was the art that should be done,” he says. “At that time, landscapes were not just out of fashion; they were looked down on. But I wasn’t really a part of that art world, so I just kept working on my landscapes.”

After seven years at the factory, Rosenthal tried his hand at fishing. As a crewman on an old trawler, he’d work four-hour shifts scanning the water for salmon and then spend eight-hour shifts in his cabin. While staring at the ocean or at rivers spilling into Bristol Bay, he began to absorb the way sunlight, shadows, and wind affected the color and texture of the water. While in his cabin, he taught himself how to use glazes, adding new layers after each shift on deck. “Fishing doesn’t seem like a good way to go for an artist, but, for me, it was pretty important,” he says.

• • •

Since 1958, the National Science Foundation (NSF) has invited select artists and writers to spend weeks or even months with American scientists living and working in Antarctica. Creatives are encouraged to help document the continent’s natural and scientific history and to share its unique geography, scenery, and climate with the rest of the world. Placements there are highly competitive—notable alumni include filmmaker Werner Herzog and writers Carl Safina and Barry Lopez.

Selected applicants get no stipend, but they receive transportation to and from Antarctica, as well as room and board in relatively spartan barracks. The biggest benefits are opportunities to hitch helicopter rides to remote scientific field stations, including regular visits to the South Pole.

Rosenthal began applying for the NSF’s Antarctic Artists & Writers Program in the late 1980s. When he failed to make the cut, he crafted an alternative plan. He got a job as a laborer, working for contractors who support scientists year-round in Antarctica. At first, he drove a forklift. Later, he was part of the team assembling field gear for researchers. Eventually, he got a chance to travel to distant scientific camps to see the terrain for himself.

“My idea,” says Rosenthal, “was that, when I became the artist in residence, I wanted to know what I was going to be dealing with and where I was going to be going. [After] the fourth application, I finally got it.”

• • •

After months of total darkness, the sun rises at McMurdo Station for about five minutes, then sets for almost 24 more hours. Within two months, the sun will shine 24 hours a day. But the light is like nowhere else on earth. “For four months, the sun just circles above the horizon,” Rosenthal says. “You can use it as a clock. If you look at my paintings and you know the terrain, you can tell what time it is, just from the shadows.”

Rosenthal paints in the realist style. Every image is exactly as he sees it, without editorializing or stylization. He puts his signature on the canvas back, not the front. “When you’re looking at one of my paintings, you’re seeing what I see in my head,” he says.

Rosenthal paints in the realist style. Every image is exactly as he sees it, without editorializing or stylization. He puts his signature on the canvas back, not the front. “When you’re looking at one of my paintings, you’re seeing what I see in my head,” he says.

To the uninitiated, his paintings resemble photographs. But Rosenthal says the differences are dramatic. The human eye processes images with a mix of bright light and deep shadows far better than a camera lens can. Our brains see colors with more nuance than do digital pixels. Light passing through a glass lens distorts perspective. After 35 years, Rosenthal prides himself on stripping a scene of distortion. Those who have seen Antarctica’s Mount Erebus tell him that his paintings capture the iconic volcano far more accurately than any photograph. “I started doing it this way because I was stubborn,” he says. “But I’ve realized over the years that that’s the key to what is valuable about my work.”

• • •

Over a 10-year stretch, Rosenthal had spent a total of 60 months, or five years, on the Earth’s southernmost continent. He was there during six Southern Hemisphere summers, five as a contract laborer and one as artist in residence. He was also there throughout four long winters, twice more as artist in residence. When temperatures reached 30 below zero with howling winds, he sketched with pen and paper, just as he did as a young man. He then reconstructed the scene from drawings and memory with oils or watercolors in the relative warmth of the indoors.

His longest continuous Antarctic stay was 16 months. “But it never felt like home,” he says, “because you’re only there by the brute force of the U.S. government and all their support.”

Nearly four decades since he first arrived in Alaska to process fish, Rosenthal’s home is still Cordova. His work has earned acclaim and respect, though not big-city exposure—not yet. He was selected as artist in residence for two national parks. He has even seen art schools soften their stance on landscape painting.

Scientists have been so impressed with Rosenthal’s Antarctic oeuvre that they’ve asked him for permission to include selections of his work in textbooks. His meticulous—if inadvertent—documentation of the retreat of remote glaciers has helped those studying the effects of climate change.

“I many times say to people, ‘I’m really lucky to be able to watch the end of the Ice Age,’ because that’s where we are,” he says. “We’re truly at the end now.”

After so many seasons in the Far North and Far South, I ask Rosenthal whether he’d like to try painting at the Equator, where the temperatures are warmer and light is radically different.

“No,” he laughs. “I hate the heat. I hate the bugs.”

THERE’S ALWAYS THE NORTH

The planet’s upper latitudes also offer opportunities for artists, including The Arctic Circle (TAC) program. Seattle’s Sadie Wechsler first heard about the program in an email to Yale’s master’s of fine art alumni. A photographer who combines images into digital collages, Wechsler—like David Rosenthal—has always been drawn to dramatic landscapes. After a bicycling trip through Iceland, she applied to a 2015 TAC expedition to the Norwegian polar island of Svalbard, located within just 10 degrees latitude of the North Pole.

“It’s very mountainous, and the mountains are tall and pointy,” she says. “Some parts remind me of formations in Utah; others look a bit like places in Iceland.” There’s very little vegetation, and polar bears roam freely.

For a photographer, the constant Arctic summer daylight presented both a challenge and a delight. “I’ve never shot with so much light before; it was amazing. I rarely needed my tripod,” she says. Even so, she admits she was often overwhelmed, unable to adequately process the sights and sounds of such a dramatically vast and barren terrain.

TAC expeditions attract a variety of creatives. Wechsler’s group included choreographers, ceramics artists, and various multimedia creators, among others. They hailed from Korea, Scotland, New Zealand, Denmark, and elsewhere. “It was amazing to watch the dancers interpret the landscape,” she says. “And it was great to be able to see where we were through so many different perspectives.”

A common interest among the artists in Wechsler’s group was the effect of climate change on Far North terrain, animals, and indigenous people. They saw plenty of icebergs and marveled as a polar bear and her cubs devoured a reindeer. But Wechsler found Svalbard locals reluctant to converse about climate. Much of the island’s economy revolves around extracting minerals from the land and fish from the sea, actions that Norwegian taxpayers heavily subsidize.

Like the NSF’s Antarctic program, TAC doesn’t pay a stipend. Unlike NSF’s program, however, TAC doesn’t provide transportation. Wechsler had to pay for her airfare of approximately $2,000 and a room, board, and travel fee of $6,000.

Now that she’s photographed the Far North, where would Wechsler like to travel next? She’s thinking of filling out an application for Antarctica.

1 Comments

Wow what amazing work.