Public authorities and private organizations work together to recover stolen art and prevent future thefts

By Melissa Hart

The Federal Bureau of Investigation estimates that thieves steal $4 billion to $6 billion worth of art worldwide each year from galleries, museums, and private homes. Some art thieves covet a particular piece and take it for their own enjoyment. Others pilfer paintings, sculptures, and

a particular piece and take it for their own enjoyment. Others pilfer paintings, sculptures, and

photographs with the intention of selling them, sometimes funding terrorist activities and other illegal pursuits with the profits. Still others—private owners—fake art theft to cash in on insurance claims. Both public and

private organizations maintain vast image databases with information on provenance and sales history of works of art and employ individuals who dedicate their days to recovering missing art.

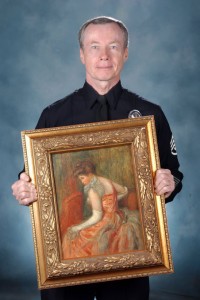

Among the organizations focused on the search and recovery of stolen art is the Art Theft Detail of the Los Angeles Police Department. It maintains a webpage that describes cases on which its detectives have worked. “These stories are presented to you for several reasons,” the website states. “First, they will give you the flavor of what it is like to be an art cop. You will see that art investigations involve many different crimes, including burglary, theft, consignment fraud, investment scams, fraudulent art, insurance fraud, elder abuse, and phony estate sales.”

One of the LAPD’s most memorable case studies, “Tibetan Artifacts and Pot-Bellied Pigs,” involved a New York City collector and scholar of Tibetan art who trusted a handyman with her keys. The man, pretending to be a student of Buddhism, stole more than 200 antiquities from her collection. Detectives received a tip 11 years later that the thief might reside in Los Angeles. They found him living in the house of a frail retiree, with some of the stolen Tibetan pieces, by then cracked and crumbling, displayed in a room. In an adjoining room, they discovered a group of pot-bellied pigs rooting around in urine and feces.

Since 1993, LAPD’s Art Theft Detail has recovered more than $121 million worth of stolen art. Many of the cases it describes are colorful—even absurd—and often preventable. Other case titles on the website include “The Chauffeur Did It,” “The Butler Did It,” and “Trust Me, I Work Here.”

“Most art theft is [done by] people who actually saw [the piece],” says LAPD Detective Brent Johnson. “It’s someone who’s been invited into the home to work.”

Databases: A Road to Recovery

Detective Don Hrycyk has been a full-time LAPD art cop for more than 20 years. When he and Johnson hear about a case of art theft, they search for fingerprints, DNA, and video footage at the crime scene. They also request high-resolution photos of the stolen piece to put up on the LAPD website. “If we think it left the country, we put it up on Interpol and Art Loss Register,” says Johnson. “Hopefully, it will come up for auction or go up for sale.”

Several databases exist worldwide to document stolen art and thwart illegal sales. Aside from those sites maintained by police departments, Interpol, and the FBI, private databases give detectives and others the ability to spread the word about new thefts and claims.

Years before the LAPD established its Art Theft Detail, the International Foundation for Art Research created an art-theft archive to curtail theft. The organization’s Stolen Art Alert became the Art Loss Register (ALR), a private database of lost and stolen art. The foundation offers both item registration and search-and-recovery services. “The ALR acts as a significant deterrent on the theft of art,” the website reads. “Criminals are now well-aware of the risk … they face in trying to sell stolen pieces of art.”

One of these pieces is Paul Cézanne’s “Bouilloire et Fruits,” a vibrant still life of apples, oranges, and lemons around a silver pitcher that was stolen from a Boston residence in 1978. It reappeared two decades later when a retired lawyer hiding his identity tried unsuccessfully to sell the painting. He demanded money from the theft victim, who then contacted the ALR. Its members worked with the FBI and Swiss police to recover the painting, which later sold for $29.3 million.

Jerome Hasler works as head of communications and strategy for Art Recovery Group (ARG), a private organization that partners with law-enforcement agencies and professionals in the international art market to reduce art theft. “Our experience has shown that the sharing of information about losses or claims is the surest way to recover works of art,” Hasler says. “That’s why we built the ArtClaim Database. We encourage loss victims and claimants to register losses for free on our database so that any attempt to sell claimed works anywhere in the world can be identified.”

In 1986, four individuals held fractional shares in Duccio di Buoninsegna’s “Madonna and Child,” a tempera and gold image that the artist painted on wood between 1290 and 1300. One of the owners vanished after stealing the painting from a bank vault in Geneva; the painting surfaced 30 years later when it was consigned for sale at Sotheby’s in New York in January 2014. The ArtClaim Database matched the painting to the stolen art, and Sotheby’s took it off the market.

Two of the surviving claimants appointed ARG, which led the resolution process with the many heirs of the original owners, according to Hasler. After successful negotiations, the United States District Court recognized the painting’s clear title in May 2015.

The staff of ARG also advises clients who receive ownership claims. In 1945, for example, Nazis seized the home and property of Viennese industrialist Julius Priester. One of the paintings stolen was El Greco’s “Portrait of a Gentleman,” painted in 1570 by the Spanish Renaissance artist. The work disappeared for almost 70 years. In June 2014, the Commission for Looted Art in Europe identified the painting, which was then for sale in a gallery. The possessing dealer hired the ARG to advise on the restitution process, according to Hasler. The painting was unconditionally restituted to Priester’s heirs in March 2015.

In 2003, thieves looted the Baghdad Museum, stealing thousands of antiquities. These thefts inspired the FBI in 2004 to establish its Art Theft Program. The program employs 13 special agents and a program manager, who accept pertinent cases referred by local police departments reporting on museum and residence thefts. They also maintain the National Stolen Art File, a database of items that are valued at more than $2,000 each.

A short video on the FBI’s website features Art Theft Program Manager Bonnie Magness-Gardiner. “We get tips from the public, and I would like to encourage the public, if they have any knowledge of stolen art, looted art, or art fraud that meets the criteria for our investigation, to submit a tip via the tip line or call their local FBI office,” she says.

Provenance: The Critical Component

Most people involved in the recovery of stolen art emphasize the important of provenance. Some artists offer a buyer’s packet to every client with a receipt and forms that prohibit the reproduction of the art. This process establishes provenance, which will likely increase the value of the artist’s artwork in years to come.

As a national fine art specialist at Chubb Insurance, Laura Doyle meets with private collectors and advises them on everything from security to packing and transit. “It really comes down to … advising the stewards of our cultural heritage,” she says. “Our clients have collections [that] encompass some of the most valuable objects in the world.”

A year ago, noting the growth of the art market over the past decade, Chubb Insurance created a formal consultation and art service program. Doyle and others went through intensive training on fine art display and the intricacies of security systems. The company maintains a relationship with the FBI and Interpol, as well as Art Recovery International and Art Loss Register. “Any reputable gallery or auction house is going to check those databases before they consign or accept consignments,” she says.

She emphasizes the importance of understanding ownership history before buying a piece of art. “Make sure the piece has clear provenance,” she says. “Most auction sales records list provenance history, including private collections and museum shows where the piece has been displayed. For pieces by living artists, you can get a certificate of authenticity. Independent provenance researchers can trace the history of a piece for you.”

Documentation and Security are Key

Doyle stresses the importance of conducting background checks on all people hired to do work in one’s home. “Keep an inventory of your collections and make sure you update it anytime an item is bought, sold, or relocated,” she says.

LAPD’s Johnson suggests how best to document art for online databases: Provide high-resolution photos of the front and back of the artwork and images of any paperwork on provenance. Documentation aside, he tells people to increase their personal home security. “A lot of people collect art, but … people [still] leave … their houses unlocked,” he says.

Security, of course, is a critical component when protecting art in private homes, museums, or galleries. “Larger-scale museums have high-end security,” Johnson says. He explains that smaller museums and galleries without large budgets are those at the greatest risk.

Burt Wolf’s Travels and Traditions on PBS includes a 19-minute “Art Cops” segment (artcops.com). The segment offers viewers a vivid sense of those professionals who work to recover stolen art. A supplemental website describes some of the most intriguing unsolved cases. One involves Lucian Freud’s small portrait of Francis Bacon, which the Tate Museum loaned to Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. The gallery hung the painting on a wall built for the exhibition. In 1988, a thief walked into the gallery, took the small portrait off a wall that hadn’t been linked to an alarm system, and walked out.

Laurie Taylor, public relations specialist at Chubb, describes a similar incident that occurred a few years ago. “Someone walked into a gallery, took our client’s consigned artwork, and walked out undetected,” she says. “The thief eventually mailed the piece back to the gallery and was subsequently caught because his fingerprints were on the artwork and he had a prior shoplifting charge.”

Sleuth around the online accounts of stolen art, and you’ll be struck by two things: First, so much of the theft is preventable. Second, the stories surrounding stolen art are often bizarre.

“We had an elderly client a few years ago with a large collection of porcelain,” Doyle says. “A handyman had worked in her home for several years. She didn’t realize that, over time, pieces from her collection were disappearing.”

The woman, hoping to sell some of her items, went online and found a website listing pieces from her collection for sale. “Working with her state’s police department, she found out who had access to her home and who had been taking the pieces,” says Doyle. “She recovered her art.”

Freelance writer Melissa Hart is the author of the memoir Wild Within: How Rescuing Owls Inspired a Family (Lyons, 2014).