by Megan Kaplon

When she began her undergraduate studies at the Columbus College of Art and Design, Soo Sunny Park planned to pursue product design. Luckily for museum visitors, however, she found her calling in sculpture and installation art. Her work is now featured at the Rice Gallery in Houston; the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts; the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, Connecticut; and other venues across the States.

Vancouver, Canada will soon have its own Park original, as the rising star completes an artist residency in conjunction with the Vancouver Biennale before returning to her home in New Hampshire. Park, who has taught at Washington University and Dartmouth College, holds an MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art. Her most recent work explores the qualities of light and the spaces in between.

We asked Park about her career path as an artist and how teaching affects her work. She offers some priceless advice for aspiring artists.

Art Business News: How did you originally become interested in art?

Soo Sunny Park: My sister and I always took art classes. I lived in Seoul, Korea until I was 9, and that’s just what you do there. You take piano lessons; you take art classes. Then I had to be apart from my parents for almost three years before I came to the States. My parents came here before my sister and I did; we had to wait until we had our green cards. Those three years of my life were just upside down. I went through crisis early. Then I moved to the U.S. to Marietta, Georgia, where I was one of the few minority kids. I think that and the language barrier and all that stuff made me the person I am, and I think it really influenced me to work with the visual because my verbal language wasn’t the strongest at that time of my life. But I didn’t really realize that until I was ready to go to college. My sister knew she was going to be an artist, so she took a portfolio class, a private lesson, and I did that, as well, and I got a really good response. I ended up going to art school with a scholarship. I did not get into the school that I wanted to go to for [math or physics], so that threw me into the art environment. I don’t regret it a bit.

ABN: Why did you decide to get an MFA degree after finishing your undergrad program?

SSP: I went to a very studious undergraduate program, the Columbus College of Art and Design, but despite that I knew that it takes a lot of discipline to be an artist. You can’t really make a living right after graduating from art school. For most artists, you have to have two jobs for a long, long time. I felt like I didn’t have the discipline to make work on my own. So I went straight to Cranbrook Academy of Art and Design for grad school.

ABN: What kind of jobs did you have when you finished grad school?

SSP: I waited tables starting when I was 14 all the way through my first year in grad school. After I finished, I told myself I can’t wait tables anymore because it’s too easy. I didn’t want waitressing to be my career, so I held off on it. I worked at a museum as a part-time preparator. Then I moved to St. Louis, and the people who I met were architects in their 40s. They were doing their office jobs, but they were also buying properties and renovating, so I was involved in that. When I had been in St. Louis for about six months, somebody called me up at the last minute, two days before school started, and asked me to teach Western art history at a community college. I jumped on it. My background is not art history; it’s studio art. So my first year was a lot of work and a lot of butterflies in my stomach, but I got over it. Then I got an offer to teach a sculpture elective at Washington University in St. Louis, which began my transition to focus more on studio art. I moved to Dartmouth, New Hampshire in 2005 [to teach studio art at Dartmouth College].

ABN: How did you learn to teach art?

SSP: I had some friends who said they wanted to teach when they were done with school, and I was like, “Are you kidding?” You have to have experience to be a mentor, so I was not for that. But when you’re out there trying to survive as an artist, a teaching opportunity is really, really great, and you can’t pass on it. When I taught the lecture course, I had to get over public-speaking fright. Then teaching studio art, I went back and thought about what I learned at Columbus College of Art and Design and structured my lessons according to the ones I thought were significant. You also learn from the students—are inspired by students. If they’re doing well, you can just see the light bulb go on, and that’s really inspiring as an artist. Another thing I love about teaching is being a part of the learning institution. It makes me do research. Say I have to talk about kinetic art with my students; I go back and do some reading, and I’m learning more about kinetic art.

ABN: What’s the most challenging thing about teaching for you?

SSP: As much as we encourage students to think outside the box and be confident about what they want to do, students do sometimes push the envelopes a little too much, and that’s hard to deal with. Also, you never know what each individual has gone through in life, so dealing with students who have emotional troubles at times is hard. Being an art teacher, you can’t separate those things as you could if you were teaching in a different discipline. Doing art, that whole creative process comes through: the visual, emotional and conceptual. You get involved more than you want to get involved. But I’m learning how to keep that divide.

ABN: How would you describe your art?

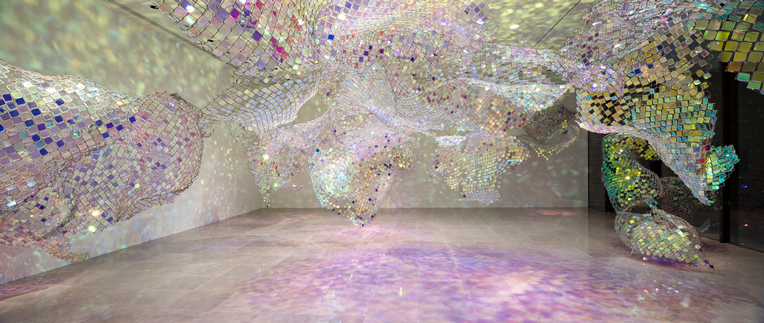

SSP: It’s really changed over the years. Now I’m making work that is not ephemeral. The object exists; it can exist for a long, long time. There is that concept of the in-between space. For the past seven years, I’ve been thinking about using light as a medium, involving natural light—daylight—so there are elements of transience and time change. Within that time change, there is a subtlety; you have the sunny day, you have the gray day, and you have the humid day, and all those things affect the mood and the projection, the reflections.

ABN: What’s your top advice for aspiring artists?

SSP: My professor from Cranbrook, Heather McGill, said to think of yourself as part of a group, not an individual doing independent things. See yourself in a larger context, how you are similar and how you are different in your approach to your work. I think that’s really great advice because, when you start making work, you want to always be making new, new, new. But in fact, a lot of things have been [created] over thousands of years of our existence. So don’t be discouraged when you find out that you’re being compared to someone else. That’s how we communicate and interact: We make references. We can’t describe something brand new without referencing something else. I also think the hard thing is to keep making work. I always say it’s a survival game. How do you survive as an artist? What is it you have to do so you don’t lose the “making” part? I give this advice to students: Think five years in advance. How do you see yourself in five years? It’s a goal, not some sort of far-fetched thing that you’re wishing for from a distance. Thinking in that way has really helped me.

For more about Soo Sunny Park, visit soosunnypark.com.

Megan Kaplon, editorial assistant at Madavor Media, has been contributing content and editorial expertise to an array of magazines since graduating from Emerson College with a degree in writing, literature and publishing.

2 Comments

Absolutely love her. Looking forward to her course in Dartmouth!

Soo Sunny,

your work is so beautiful.

I love that you have a background in physics but ended up ultimately creating art.

I wish I could have visited your exhibit!